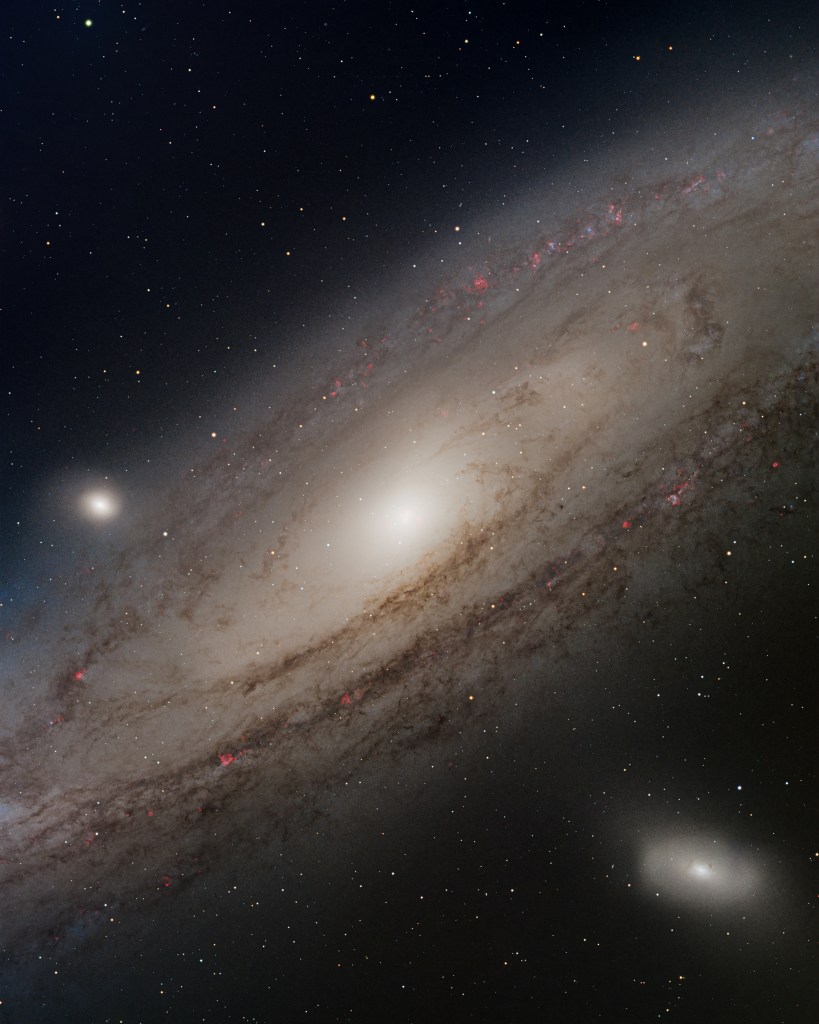

Every amateur astronomer has looked at or imaged the Andromeda Galaxy. Most, like me, have returned to it more than once. Despite it (really because of it) being the largest, closest non-satellite galaxy in our sky, it is challenging too process. There is so much dynamic range from the center to the edges.

This data comes from a telescope run by a friend who imaged this in 2022 from the same observatory in Texas I have been fortunate to have access to. He was actually using a telescope I was able to use in 2020 when it was in West Virginia. M31 is so big, it doesn’t quite fit in the field of view but the scope resolved an amazing amount of detail.

M31 is big enough (about the width of six full moons) and bright enough that you can see it with the unaided eye if the sky is dark enough. It’s an excellent binocular object though in most amateur telescopes it’s less inspiring as a visual target unless you have a nice, dark sky and a large aperture. For the imager, it’s a delight in any scope.

The two bright “blobs” are satellite galaxies of M31. The top left is called Messier 32 and the bottom right is Messier 110. They are to the Andromeda Galaxy what the Magellanic Clouds are to our Milky Way.

Capturing the diffuseness of the “edge” of a galaxy can be challenging but there was enough data in this set to show the diffuseness at the “edge”. Try looking at the image full screen and sitting back. The fuzzy “edge” should pop out at you.

This was 111h 10m of RGBo data. For the technical details, see astrobin.